Posted13 Feb 2015

- In

The Art of Darkness - Guest Post by John Cooper

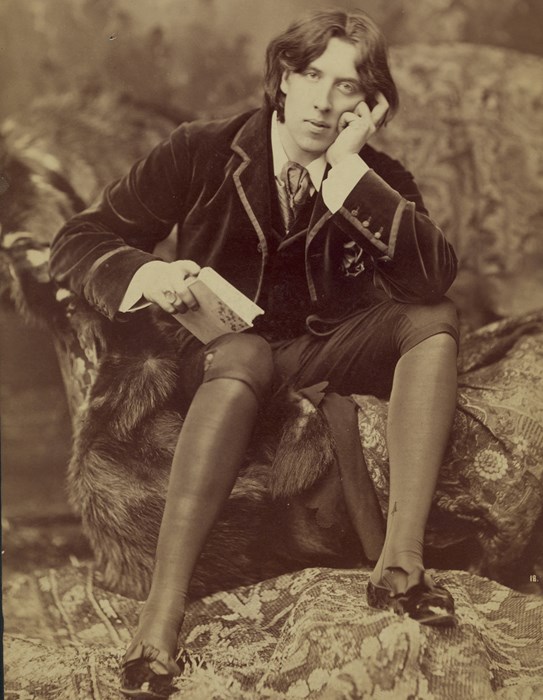

The last time Oscar Wilde visited Philadelphia it was to promote an opera. That was during a lecture tour of America in 1882 when a required part of his raison d’être was to be the poster-boy for Gilbert & Sullivan’s latest offering Patience—a comic opera whose purpose was to ridicule the adherents of the Aesthetic Movement. Not that it mattered to Oscar Wilde that he was the movement’s leading representative and the person most closely identified with the ridicule. He always knew he would outlive the mob mentality, and it is an ironic measure of the wisdom of Wilde’s indifference that he has triumphantly returned to Philadelphia as the subject of an opera himself. The question now is: if Oscar the man was indifferent to Patience, would he have had any patience for Oscar the opera?

To a large degree the question is moot. There is no evidence that Wilde was a great lover of music, although he did, of course, attend grand theatrical occasions including the opera. For instance, while in America he took the time to meet the highly acclaimed Italian opera singer Adelina Patti who, like Wilde, was a client of the theatrical impresario Richard D'Oyly Carte. The composer Giuseppe Verdi, writing in 1877, described her as perhaps the finest singer who had ever lived. That night Wilde heard her sing “Bel Raggio" from Semiramide by Rossini (see my chronicle at Patti in Cincinnati).

But whatever Wilde thought of music and singing (and it is my belief he would have thought highly of them in Oscar), he would certainly have recognized the opera production as Art. This is due entirely to the fertile imagination of composer and librettists Theo Morrison and John Cox, whose creative instinct to artistically distort imagery in Oscar is entirelyWildean.

In his essay, The Decay of Lying, Wilde said that “no great artist ever sees things as they really are. If he did, he would cease to be an artist…it is style that makes us believe in a thing”. He gave the example of Holbein’s two-dimensional representations that we recall of Tudor nobility, never mind that Henry VIII did not really look like that. Similarly, no one noticed London fogs until they were painted by the Impressionists who had shown us the mysterious loveliness of their effects. A modern version of the theme may be that Andy Warhol’s silkscreen vision of Marilyn Monroe will remain recognizable longer than any photograph. Life imitates art, Wilde said, far more than art imitates life. The idea is perhaps best summed up in a story Wilde told of a man who was asked by a hostess at a party to come to the window to see a glorious sky, only for him to respond that yet another sunset in nature was nothing more than a very second-rate Turner.

If we translate Wilde’s painterly allusions to the opera stage, we see that the same is true of Oscar. The opera commendably takes the same artistic license in its staging to present things as they are not, or as Wilde called it: to use the imagery of the beautifully untrue, which is the proper aim of Art.

Most vivid is the true-life scenario when Wilde was forced into hiding, during his trials, to stay overnight in the nursery of his friend, Ada Leverson. Morrison and Cox conflate the settings of courtroom and nursery by reimagining the judge and jury at Wilde’s trials as Oscar’s playthings; the toys come to life in a clever and long overdue satire of those who condemned Wilde to prison and an early death. Posterity will again be best served if life imitates art. We should now think of Wilde’s judge, Mr Justice Wills, only as a listless and ludicrous jack-in-a-box, and henceforth we can adopt the metaphor of the opera and gleefully shut the lid on his homophobic pontificating.

In the opera we also have Wilde’s lover and nemesis, Alfred Douglas, whose role in the Wilde story as homme fatale is brilliantly realized as a dancer only: a silent sprite flitting around Wilde as both irritant and muse. He completes the role in the guise of the grim reaper of Wilde’s demise, in which embodiment, the character’s movements recall the skeletal Danse Macabre that Wilde describes on the window blind in his poem The Harlot’s House, where:

the ghostly dancers spin

To sound of horn and violin,

Like black leaves wheeling in the wind.

The allusion reminds us that Oscar the opera is a dark piece. This approach is entirely legitimate as many people begin but also end their experience of Wilde with his classic comedies. It is impossible to avoid the lightness in Wilde (and the opera has several amusing moments, all of them Wildean), but it is salutary to be reminded that Wilde’s life was ultimately sad.

If you wish to meet Wilde you will be attracted by the bon mots and aphorisms of his life; but if you wish to know Wilde you must also understand the pain and pathos of his death. This is why the opera depicts Wilde not in the drawing rooms of his comedies but in the courtroom and prison cell of his tragedy. So go to Oscar for the music and singing, but do not overlook that a gay and gentle man is superimposed onto the art of darkness. The prison yard hanging of a fellow inmate; the starving of little boys; the latrine atmosphere of the tiny cell, the cruel regime of privation; the torture of hard labor. It will then resonate how far we have come in rehabilitating Wilde from social pariah to thinker and moralist.

The rehabilitation that currently resonates from in Oscar is the triumph of Wilde’s sexual identity. In an era of same-sex marriage, Wilde’s own heterosexual marriage is noticeable by its absence from the opera. I suspect this is deliberate, and an artistic decision. It doesn’t trouble me: any chronicler of Wilde’s life should welcome a further artistic stepping stone in the cultural shift. It is another snub to the ignorance of Victorian courts and prisons. It would not have troubled Wilde, either. He was a man possessed of insight into the relation of art and life. Indeed, apropos The Decay of Lying, he posited that art was not a mirror to life —it was a veil through which we see it. But it is also true of Wilde that personality was a veil to lifestyle. So it is ironic, and fittingly inverted, that when the English judicial system denied Wilde that veil, it revealed a personality that was to become a mirror in which the law would one day see reflected its own face of prejudice.

About the Author

John Cooper is a documentary historian and scholar who has spent 30 years in the study of Oscar Wilde. He is a long-standing member of the Oscar Wilde Society in London, a founding member of the Oscar Wilde Society of America, and a former manager of the Victorian Society In America. He lectures on Wilde and is a contributor to academic journals including The Wildean and Oscholars. Online he is a blogger and the author/editor of the noncommercial archive Oscar Wilde in America. For the last 13 years he has specialized in new and unique research into Oscar Wilde in New York, where he conducts guided walking tours based on the visits of Oscar Wilde. In 2012 John rediscovered the essay The Philosophy Of Dress by Wilde that forms the centerpiece to his book Oscar Wilde On Dress (2013).

John Cooper is a documentary historian and scholar who has spent 30 years in the study of Oscar Wilde. He is a long-standing member of the Oscar Wilde Society in London, a founding member of the Oscar Wilde Society of America, and a former manager of the Victorian Society In America. He lectures on Wilde and is a contributor to academic journals including The Wildean and Oscholars. Online he is a blogger and the author/editor of the noncommercial archive Oscar Wilde in America. For the last 13 years he has specialized in new and unique research into Oscar Wilde in New York, where he conducts guided walking tours based on the visits of Oscar Wilde. In 2012 John rediscovered the essay The Philosophy Of Dress by Wilde that forms the centerpiece to his book Oscar Wilde On Dress (2013).

Comments are closed.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter More

More