Posted31 Aug 2017

- In

A Magical Storybook

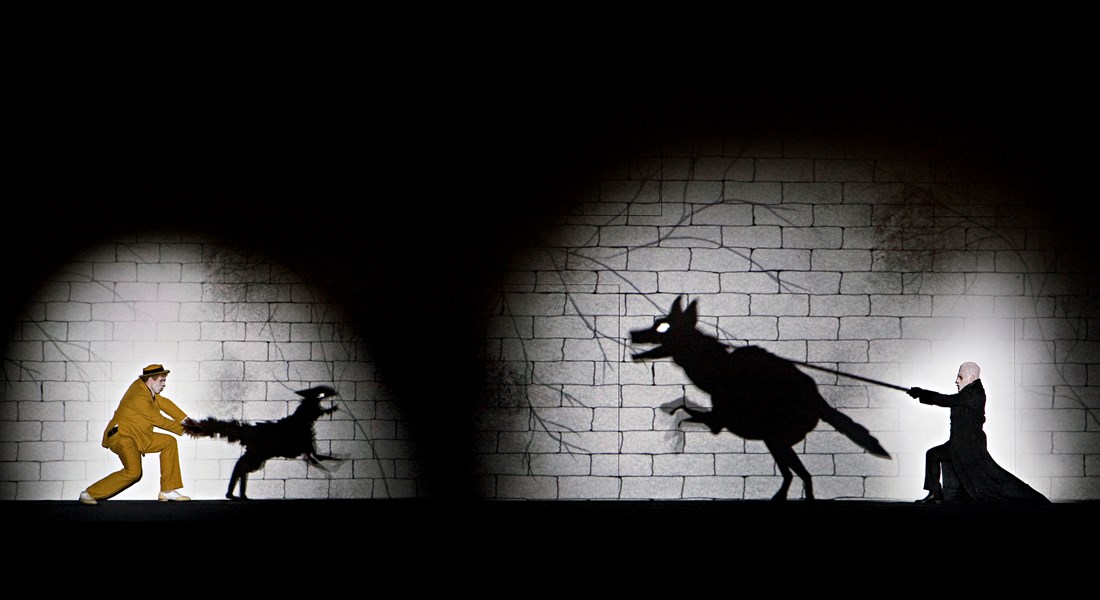

The Magic Flute is a roaring-twenties set vision. It has the beauty of a classic silent film, but live. Here, the production team – Suzanne Andrade, Barrie Kosky, and Paul Barritt – talk about the concept behind their vision for Mozart’s fantasy opera.

How did you come up with the idea of staging The Magic Flute with 1927?

Barrie Kosky (stage director; Intendent of the Komische Oper Berlin): The Magic Flute is the most frequently performed German-language opera, one of the top ten operas in the world. Everyone knows the story; everybody knows the music; everyone knows the characters. On top of that, it is an “ ageless” opera, meaning that an eight-year-old can enjoy it as much as an octogenarian can. So you start out with some pressure when you undertake a staging of this opera. I think the challenge is to embrace the heterogeneous nature of this opera. Any attempt to interpret the piece in only one way is bound to fail. You almost have to celebrate the contradictions and inconsistencies of the plot and the characters, as well as the mix of fantasy, surrealism, magic, and deeply touching human emotions. About six years ago, I attended a performance of Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea, the first show created by the British theater company known as 1927. From the moment the show started, there was this fascinating mix of live performance with animation, creating its own aesthetic world. Within minutes, this strange mixture of silent film and music hall had convinced me that these people had to do The Magic Flute with me in Berlin! It seemed to me quite an advantage that Paul and Suzanne would be venturing into opera for the first time, because they were completely free of any preconceptions about it, unlike me. The result was a unique Magic Flute. Although Suzanne and Paul were working in Berlin for the first time, they had a natural feel for the city’s artistic ambiance, especially the Berlin of the 1920s, when it was such an important creative center for painting, cabaret, silent film, and animated film. Suzanne, Paul, and I share a love for revue, vaudeville, music hall, and similar forms of theater, and, of course, for silent film. So our Papageno is suggestive of Buster Keaton, Monostatos is a bit Nosferatu, and Pamina perhaps a bit reminiscent of Louise Brooks. But it’s more than an homage to silent film—there are far too many influences from other areas. But the world of silent film gives us a certain vocabulary that we can then use in any way that we like.

Is your love of silent film the motivation behind the name 1927?

Suzanne Andrade (stage director/writer/performer; co-creator of 1927): 1927 was the year of the first sound film, The Jazz Singer with Al Jolson, an absolute sensation at the time. Curiously, however, no one believed at that time that the talkies would prevail over silent films. We found this aspect especially exciting. We work with a mixture of live performance and animation, which makes it a completely new art form in many ways. Many others have used film in theater, but 1927 integrates film in a very new way. We don’t do a theater piece with added movies. Nor do we make a movie and then combine it with acting elements. Everything goes hand in hand. Our shows evoke the world of dreams and nightmares, with aesthetics that hearken back to the world of silent film.

Paul Barritt (filmmaker; co-creator of 1927): And yet it would be wrong to see in our work only the influence of the 1920s and silent film. We take our visual inspiration from many eras, from the copper engravings of the 18th century as well as in comics of today. There is no preconceived aesthetic setting in our mind when we work on a show. The important thing is that the image fits. A good example is Papageno’s aria “ Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen” [a girl or a little wife]. In the libretto, he is served a glass of wine in the dialogue before his aria. We let him have a drink, but it isn’t wine. It’s a pink cocktail from a giant cocktail glass, and Suzanne had the idea that he would start to see pink elephants flying around him. Of course, the most famous of all flying elephants was Dumbo—from the 1940s—but the actual year isn’t important as long as everything comes together visually.

S: Our Magic Flute is a journey through different worlds of fantasy. But as in all of our shows, there is a connecting style that ensures that the whole thing doesn’t fall apart aesthetically.

B: This is also helped by 1927’s very special feeling for rhythm. The rhythm of the music and the text has an enormous influence on the animation. As we worked together on The Magic Flute, the timing always came from the music, even—especially—in the dialogues, which we condensed and transformed into silent film intertitles with piano accompaniment. However, we use an 18th century fortepiano, and the accompanying music is by Mozart, from his two fantasias for piano, K. 475 in C minor and K. 397 in D minor. This not only gives the whole piece a consistent style, but also a consistent rhythm. It’s a silent film by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, so to speak!

Does this piece work without the dialogues?

S: I think that almost any story can be told without words. You can undress a story to the bone, to find out what you really need to convey the plot. We tried to do that in The Magic Flute. You can convey so much of a story through purely visual means. You don’t always need two pages of dialogue to show the relationship between two people. You don’t need a comic dialogue to show that Papageno is a funny character. A clever gimmick can sometimes offer more insight than dialogue.

P: Going back to silent films, for a moment—they weren’t just films without sound, with intertitles in place of the missing voices. Intertitles were actually used very sparingly. The makers of silent films instead told their stories through the visual elements. While talkies convey the stories primarily through dialogue, silent films told their story through gestures, movements and glances, and so on.

B: This emphasis on the images makes it possible for every viewer to experience the show in his or her own way: as a magical, living storybook; as a curious, contemporary meditation on silent film as a singing silent film; or as paintings come to life. Basically, we have a hundred stage sets in which things happen that normally aren’t possible onstage: flying elephants, flutes trailing notes, bells as showgirls... We can fly up to the stars and then ride an elevator to hell, all within a few minutes. In addition to all the animation in our production, there are also moments when the singers are in a simple white spotlight. And suddenly there’s only the music, the text, and the character. The very simplicity makes these perhaps the most touching moments of the evening. During the performance, the technology doesn’t play in the foreground. Although Paul spent hours and hours sitting in front of a computer to create it, his animation never loses its deeply human component. You can always see that a human hand has drawn everything. Video projections as part of theatrical productions aren’t new. But they often become boring after a few minutes, because there isn’t any interaction between the two-dimensional space of the screen and the three dimensions of the actors. Suzanne and Paul have solved this problem by combining all of these dimensions into a common theatrical language.

What is The Magic Flute really about?

P: It’s a love story, told as a fairy tale.

S: The love story between Tamino and Pamina. Throughout the entire piece, the two try to find each other—but everyone else separates them and pulls them away from each other. Only at the very end do they come together.

B: A strange, fairytale love story, one that has a lot of archetypal and mythological elements, such as the trials they must undergo to gain wisdom. They have to go through fire and water to mature. These are ancient rites of initiation. The Masonic trappings imposed on the story interested us very little, since they have, of course, much, much deeper roots. Tamino falls in love with a portrait. How many myths and fairy tales include this plot point? The hero falls in love with a picture and goes in search of the subject. And on his way to her, he encounters all sorts of obstacles. And, at the same time, the object of his desire faces her own personal obstacles on her own journey. You can experience our production as a journey through the dream worlds of Tamino and Pamina. These two dream worlds collide and combine to form one strange dream. The person who combines these dreams and these worlds is Papageno. We are very focused on these three characters. Interestingly, Papageno is in pursuit of an idealized image too: the perfect fantasy woman at his side, something he craves almost desperately. Despite all of the comedic elements, there is a deep loneliness in The Magic Flute. Half of the piece is the fact that people are alone: Despite the joy in Papageno’s bird catcher aria, it’s ultimately about a man who feels lonely and longs for love. At the beginning of the opera, Tamino is running alone through the forest. The three ladies are alone, so they are immediately attracted to Tamino. The Queen of the Night is alone—her husband has died and her daughter has been kidnapped. Even Sarastro, who has a large following, has no partner at his side. Not to mention Monostatos, whose unfulfilled longing for love degenerates into unbridled lust. The Magic Flute is about the search for love, and about the different forms that this search can take.

Leave your comment below.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter More

More