Posted21 Sep 2023

- In

Paving new paths for women, from journalism to opera

Ophelia stands on the banks of a lake, driven to the brink by the cruelty of her would-be husband. She wears an intricate gown with a V-shaped collar dipping almost daringly low, the striking bone structure of her face framed with ringlets, her hair piled high and adorned with flowers. She sings mesmerizing coloratura vocal lines, delicate but frightening, suspenseful, haunting, as she drowns herself.

This is famed soprano Christine Nilsson in the "mad scene" at the 1868 premiere of Ambroise Thomas' Hamlet, based on an Alexandre Dumas interpretation of the Shakespeare play with a libretto by Michel Carré and Jules Barbier. Like in the painting by John Everett Millais 15 years earlier, her madness is enticing.

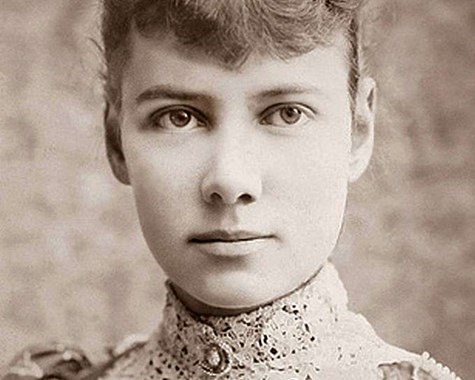

A woman driven to suicidal madness, depicted in writing, painting, staging, and music by men, is a beautiful thing. This was the world in which Nellie Bly, born 1864, grew up.

In the 1800s, there were women in journalism, but they were largely relegated to writing for the women's pages about fashion and society, explains Brooke Kroeger, author of Nellie Bly: Daredevil, Reporter, Feminist. Bly encountered this barrier but forcefully and courageously found a path for herself in investigative journalism with the 1887 "Ten Days" exposé. By proving women could report and that their reporting could sell papers, "what she did was open a field that was off the women's pages," says Kroeger.

Bly's reporting helped the women she wrote about in the asylum by leading to a grand jury investigation and subsequent increase in funding. But she also helped other women gain opportunities in journalism. Editors saw there was interest in investigative stories about women in places only women could access and thus followed "a decade of opportunity" for female journalists, according to Kim Todd, author of Sensational: The Hidden History of America’s "Girl Stunt Reporters."

"All of a sudden, you had not just the women’s page with the reports on ballgown styles and not just the stories of women getting murdered, which was often how they got on the front page,” Todd said. “You had women writers doing brave things and uncovering abuses.”

Meanwhile, women were still wearing ballgowns and getting murdered, over and over again, onstage in opera houses. There were some women composers, but aside from singers, opera and classical music was overwhelmingly male, as society women were still expected to be only homemakers and mothers. In the early 1800s, Fanny Mendelssohn was pressured to hide her musical talents, publishing some works under her brother's name, because composition wasn't considered an acceptable profession for a woman. Exceptionally, Clara Schumann, who came a few decades later, pushed forward with a professional career as a musician and composer.

In 1903, the Metropolitan Opera premiered its first opera composed by a woman, Der Wald by Ethel Smyth. Smyth, like Bly, was a force. The English composer went on to join the women's suffrage movement, writing music in its honor and getting arrested, along with 100 others, at an incident involving throwing stones at anti-suffrage households. Per her New York Times obituary in 1944, while jailed, "she used her toothbrush as a baton through the window of her cell to conduct the singing of her fellow suffragettes" to the tune of her "March of the Women."

Although she continued composing, no more of Smyth's work would be performed at the Met after Der Wald, which the Times dismissed as "a disappointing novelty." In fact, although women were composing music throughout the 1900s as more women entered musical professions and conservatories, it would take more than a century for the Met to premiere its second opera composed by a woman, L’Amour de Loin by the late composer Kaija Saariaho, who told the Times, "It just shows how slowly these things evolve."

Even today, women are still only coming to be accepted as composers, conductors, and directors. A production like 10 Days in a Madhouse, with a fully female creative team, is unusual to see. Composer Rene Orth isn't sure how to talk about the experience of being in an all-female creative team, but she knows "people wouldn't ask, if I were a man, 'How does it feel to be on an all-male team?'"

Since the 1880s, women have become more normalized in journalism, if not entirely dominant. Nearly a third of Pulitzer Prizes for journalism were won by women between 2007 and 2016, according to the Columbia Journalism Review, a big jump from previous decades. New York Times reporter Susanne Craig won one in 2019, and though her investigative work looks different than Bly's, "certainly we stand on her shoulders; we all do," she says.

Craig earned the first Nellie Bly Award for Investigative Reporting from the Museum of Political Corruption in 2017. She says she isn't always sure about the role of her own gender in her work, which often centers on male-dominated fields like politics and finance, dealing with machismo figures like the Trumps and Cuomos of the world. You wonder, she says, and you know it has an impact, but "sometimes you just don't know more than anything if it's helping or hurting."

A homemade action figure of Bly sits on Craig’s desk. The little figurine beams determination in stitched eyes, sporting a blue cloth dress and herringbone jacket. It was made by a student of Bruce Roter, the music professor who founded the Museum of Political Corruption, which doesn't exist—yet—in brick-and-mortar, but was inspired by Albany's history of governmental corruption. Bly reported on Albany's corruption in her day by, naturally, bribing politicians.

Orth was inspired to write an opera about Bly's "Ten Days" in part because it's a great story, in part because the abuse and mistreatment of women in medical facilities is still going on today, and, yes, in part because "opera has an obsession with madness," she says. But this opera isn't the male fantasy depiction of a manic pixie dream girl gone mad. The creative team, she says, approached the story with empathy as "we all absolutely can identify with some part of the opera, somehow we feel it a part of ourselves."

Thanks to pioneers like Bly and Schumann, women have become more common figures in journalism and opera over the last century and a half, and thankfully the medical field has developed a better understanding of mental illness, trauma, and treatment. But we're not yet in an equality utopia.

"Abuse is still a thing, trauma is still a thing," Orth says, "but what we rarely see onstage is women rising above that. They may not conquer it, but they still are strong and they still go on and push forward."

Alexandra Svokos, MBA, is the senior digital editor of the financial magazine Kiplinger. She admittedly had Natalie Dessay's Mad Scenes CD on rotation in her car through high school.

This essay is part of the O23 Festival Book.

Leave your comment below.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter More

More